Eugene McCabe is one of Ireland's leading playwrights and is known especially for his play The King of the Castle. He wrote Pull Down a Horseman in 1966, when he was in his mid-thirties, to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Rising. He was born on 7 July 1930 in Glasgow, but grew up and lived most of his life in Clones, County Monaghan, on a farm just 400 metres from the border with Northern Ireland. He died on 27 August 2020.

Pull Down a Horseman enacts a private meeting between Patrick Pearse and James Connolly on whether and when to go ahead with the Rising. Such a meeting did take place in the house of an IRB member in Dolphin’s Barn, Dublin over three days from Wednesday 19 January 1916. Connolly was invited to attend the meeting with senior leaders within the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) including Patrick Pearse.

The objective of the meeting was to persuade Connolly to join the others rather than pursue his own plans, which he was keen to do, because he feared that British Intelligence could soon discover what was planned. As Conor O'Malley, director of this production, has noted "It would have been great to have been a 'fly on the wall', to have listened to the conversation". This play gives a wonderful opportunity to do just that. It is presented by two actors and in the dramatic conflict that comes from the expression of their different political philosophies and perspectives, we gain an insight into the characters of the two men and what they thought and felt about the issues that led to the Rising.

The play condenses the role of the Irish Republican Brotherhood to a meeting between Connolly and Pearse. It is presented in one act and runs for just over half an hour. It begins by introducing the political ideas of the two men through their writings, and pitches them against each other, which provides a context for what follows. Their characters are revealed through their interaction, their argument, debate and sharing of personal feelings, hopes and aspirations. That part of the play is described by the director as "hard-knuckle stuff — this is a frank conversation — hard-hitting and frank in their exchanges".

The short four-minute video (above) is an edited version of a longer interview with the director, Conor O'Malley, which is also on this page. The recording was made in Pearse's study at St Enda's School. The building, which was the boy's school he established, is now the Pearse Museum in Rathfarnham, Dublin. Access to St Enda's was facilitated by the Office of Public Works.

Performances of Pull Down a Horseman in 2016

After a short introduction, the play ran for about forty minutes and, with the exception of some lunchtime performances, was followed by a post-show discussion. Patrick Pearse was played by Declan Brennan and James Connolly was played by MJ Sullivan.

(l-r) Conor O'Malley (Director), Declan Brennan (Pearse), President Michael D Higgins, Mrs Sabina Higgins, MJ Sullivan (Connolly) at a performance of 'Pull Down a Horseman' on 9 February 2016 in Áras an Uachtaráin, the official residence of the President of Ireland, in the Phoenix Park, Dublin.

Dublin Lyric was invited to stage a performance of Pull Down a Horseman for President Michael D Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin in February 2016.

The President and Mrs Higgins invited Eugene McCabe and his wife, Margot, to see the play in the official residence. They joined the staff of the Áras and invited guests for the performance, which was followed by a lively and very interesting discussion.

The State Reception Room, where we performed, dates from 1802 and was originally the ballroom of the house. It was a very special occasion, performing surrounded by that audience and on the magnificent handwoven Donegal carpet with the image of the phoenix rising from the flames at its centre.

An interview with Conor O'Malley, Director of Pull Down a Horseman

The Office of Public Works kindly made the facilities at St Enda's Park available for the recording of an interview with the director of Pull Down a Horseman, Conor O'Malley. The assistance of the Curator of the Pearse Museum at St Enda's, Brian Crowley, was greatly appreciated.

In this interview Conor talks about the play and puts it in the wider context of political drama, the characters of Pearse and Connolly, and the modern relevance of a play written 50 years after the events of 1916 and 50 years before these performances in 2016.

He describes how the opening few minutes of the play are in the form of expressionist theatre, where the political ideas of Pearse and Connolly are pitched against each other through their writings, before going straight into the main action of the play, where the flesh and blood characters of the two men are revealed in the following 35 minutes.

The interview was recorded in Patrick Pearse's study and the video shows other parts of the building and the grounds, which were home to the Irish school established by Pearse and which are now home to the Pearse Museum. The contrast between the backgrounds of the two men, and their different thinking, positions them far apart from one another when the play opens. However, as Conor notes "at the end of the play, there's a respect between Connolly and Pearse which you could hardly imagine as they begin their conversation". His view is that a great strength of the play comes from how it presents these differences in a way that promotes further discussion and without drawing conclusions. It is left to us, the spectators, to examine these men and the events they shaped. We can do it with the benefit of 100 years of hindsight as we revisit them — imaginatively — through this play. And as Conor concludes, "we must make of it as we will in 2016".

RTÉ Radio 1 'Arena' arts show

Seán Rocks interviewed Conor O'Malley about the play during an edition of the RTÉ Radio 1 arts show 'Arena' that was broadcast on Friday 5 February 2016. A recording of that interview, including a short extract from the beginning of the play, is in the audio player above.

Past Performances

The play was first performed by Dublin Lyric in the National Library, Kildare Street, Dublin and later in the National Museum, Benburb Street, Dublin. The old Collins Barracks, which are now the museum, were home to soldiers (first British and then Irish) for 300 years. Both of these venues were included in the schedule of performances for 2016, the Centenary year of the Easter 1916 Rising

Playwright Eugene McCabe (centre) and MJ Sullivan with Mrs Sabina Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin on 9 February 2016.

Playwright Eugene McCabe (centre) and MJ Sullivan with Mrs Sabina Higgins at Áras an Uachtaráin on 9 February 2016.The Dublin Lyric production in 2007 is believed to have been the first performance of this play since a presentation in the Peacock at the Abbey Theatre in 1979.

The very first performance was on 17 April 1966 in the Eblana Theatre, Dublin in a presentation by Gemini Productions, which featured T.P. McKenna as P. H. Pearse and Niall Tóibín as James Connolly. It was then staged in the Peacock at the Abbey Theatre for six performances, from Monday 21 August 1972, with Bosco Hogan playing Pearse and Michael Duffy as Connolly. It was one of two plays performed on those nights, the other being They Feed Christians to Lion Here, Don't They. Seven years later, as part of the Pearse Centenary celebrations, it was back in the Peacock for 15 performances from Thursday 29 November 1979 with Desmond (Des) Cave as Pearse and Peadar Lamb as Connolly. The play performed with it on those nights was Gale Day by Eugene McCabe, an Abbey/ RTÉ co-production. As far as we are aware it was rarely, if ever, produced after that until the first performances by Dublin Lyric in 2007 with Declan Brennan as Pearse and Alan Carey as Connolly.

The script of Pull Down a Horseman was published by The Gallery Press in 1979 with Gale Day, which was commissioned by the Abbey Theatre and RTÉ to commemorate the centenary of Patrick Pearse's birth.

Actors and Director

The photograph below was taken when the team behind this production visited the Pearse Museum for the recording of the short four minute introductory video and the video discussion of the play by Conor O'Malley.

(l-r) MJ Sullivan, Conor O'Malley and Declan Brennan at the Pearse Museum in St Enda's Park, Rathfarnham, Dublin

(l-r) MJ Sullivan, Conor O'Malley and Declan Brennan at the Pearse Museum in St Enda's Park, Rathfarnham, DublinConor O'Malley, director of Pull Down a Horseman, established Dublin Lyric in 2005. He has had a lifelong interest and involvement in theatre from his early training with the Lyric in Belfast and with the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, to his involvement with the Adult Education Department in UCD over a 20 year period, where he gave many theatre courses. His directing credits include Brecht’s Mother Courage, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, The Caucasian Chalk Circle, Sobol’s Ghetto, O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars, Juno and the Paycock, The Silver Tassie, Red Roses for Me, Arms and the Man, Galvin’s The Last Burning, The Heart's A Wonder, Sam Thompson’s The Evangelist, The Colleen Bawn, Peer Gynt, an adaptation of Finnegans Wake and new plays There's Nobody Mad Here and Marty's Shot by Armagh based writer, Joe Ruane.

Conor has had a stint as Director of Strategy at Culture Ireland and, in a parallel existence, contributes to the conservation of the natural heritage.

MJ Sullivan as Connolly

MJ Sullivan as ConnollyMJ Sullivan (James Connolly) is from inner city Dublin and has been acting for the past 28 years. Favourite roles on stage have been Nick in The Last Apache Reunion by Bernard Farrell, Sagredo in The Life of Galileo by Brecht, The Bishop in Within the Gates by Sean O’Casey, Theseus in Oedipus at Colonus by Sophocles, Dr. Rank in A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen, Jimmy Perry in The Gingerbread Lady by Neil Simon, Parris in The Crucible by Arthur Miller and Alfieri in A View from the Bridge by Arthur Miller.

Michael has also worked in film with independent film makers and the students from various colleges around Ireland. His first feature film, Nameless, is scheduled for release in 2016.

Declan Brennan as Pearse

Declan Brennan as PearseDeclan Brennan (Patrick Pearse) has played characters in the ancient and modern theatre — from Sophocles through Shakespeare to Neil Simon. The wide range of genres and writers spanned include Yeats, Brecht and Eugene McCabe for Dublin Lyric. From the plays of Shakespeare he has had roles in Macbeth, Othello, King Lear and Hamlet for Mill Productions. Ten years ago he played the Narrator in Our Town by Thornton Wilder, which opened the Mill Theatre. More modern roles have included Victor Velasco in Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park at Andrews Lane Studio and Smock Alley Theatre, the iconic doctor in Albert Einstein meets Dr Who by Justin Richards at the Young Scientist Exhibition in the RDS, Dublin, the Professor in David Mamet’s Oleanna and Tomás McDonagh in Seven Lives for Liberty by Frank Allen. And he has performed readings from Joyce’s Ulysses on Bloomsday.

Declan's technical work includes photography and sound design and he also works on voice-over and narration for broadcast and other media (declanb.com). He holds an MA in Drama and Performance Studies from University College Dublin.

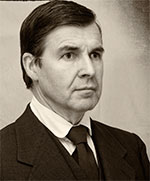

Patrick Pearse (1879-1916)

Patrick Pearse described himself, in an unpublished autobiographical piece, as the ‘strange thing that I am’.

Patrick Pearse

Patrick Pearse 10 November 1879 to 3 May 1916

He was born in Dublin, to an Irish mother and a father, who was a self-educated, free-thinking sculptor from England, specialising in ecclesiastical work. Patrick was an intelligent and diligent student; and he won a scholarship to the Royal University where he studied law and was later called to the bar. After he left school, he joined the Gaelic League and became committed to the revival of the Irish Language and to educational reform. In the beginning he was more interested in education than political independence. The independent Irish-speaking school that he established in 1908 for boys in Dublin, St. Enda’s, was a place where the pupils were expected to "work hard [...] for their fatherland, and if it should ever be necessary [...] die for it".

As Pearse became more political, he also came to agree with physical force as a way to achieve the aims of republicanism. He also came to see a ‘blood sacrifice’ as a necessary means to that end.

After joining the Irish Volunteer Force, when it was founded in November 1913, he was quickly promoted to a staff position at headquarters. When he spoke at the commemoration of Wolfe Tone’s death in 1913 and at the graveside of O’Donovan Rossa in 1915, he impressed the leaders of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) who were engaged in secretly organising the Easter Rising. As a member of that planning group, he worked on acquiring German arms, he negotiated with Connolly (the subject of this play), he dealt with the volunteers and he kept Eoin MacNeill (who opposed those plans) in the dark about what was being done. His skill was with a pen rather than a sword; and he used that skill to mobilise support and to justify the rebellion. He was appointed Commandant-General of the Army of the Irish Republic and President of the Provisional Government, which he proclaimed outside the General Post Office (GPO) on the following day, 23 April 1916.

Pearse was at the GPO during Easter week. While he was in command, and represented a calm presence by all accounts, it is unlikely that he fired a single shot, and more likely that James Connolly handled the finer points of military organisation. In spite of his belief in the concept of blood sacrifice, the cruel and ugly reality of it did not sit easy with him, especially when he saw the toll it took on the civilian population. He said, "When we are all wiped out, people will blame us. [...] In a few years they will see the meaning of what we tried to do." He was one of the last to leave when the shells fired by the British Army set the GPO on fire. At noon on the following day, he surrendered on behalf of the other leaders to Brigadier-General Lowe and he was court-martialled at Richmond Barracks on 2 May. He positioned himself as the main leader of the insurrection and asked that his men should be spared. At his court martial, he was found guilty, sentenced to death and transferred to Kilmainham Jail, where he spent some time writing before his execution. What he wrote then and the role he played during Easter week secured his position as an iconic hero in the minds of many people to this day.

The execution of Patrick Pearse and the other 15 men condemned to death for their involvement in the Rising, made them martyrs, something which he seemed pleased to leave behind. In a letter to his mother, he wrote: 'This is the death I should have asked for if God had given me the choice of all deaths'.

Pearse was shot by firing squad in the early hours of 3 May 1916 and was buried at Arbour Hill Barracks.

David Thornley writing about Patrick Pearse in 1971

My instinct [when asked in 1965 to prepare a Commemorative of the 1916 Rising for RTÉ Radio] was to refuse, for three reasons. First, I felt better able by knowledge and sympathy to talk about Connolly. Secondly, I knew that anyone who talks about Pearse in Ireland with any degree of frankness violates a shrine more sacred even than Tone's, Emmet's, or John F. Kennedy's. Thirdly, at that time, I just did not like the man. The Pearse presented by Le Roux in his biography as a knight without reproach always appeared to me incredibly two-dimensional. The Pearse who believed in an Ireland not free merely but Gaelic-speaking also seemed to me incredibly unrealistic and the Pearse who spoke of warming the old heart of the earth with the red wine of the battlefields seemed to me to verge on the hysterical. With reluctance I embarked on the commission and found my view to be slowly changing. I found that Pearse had an English father who died when he was very young. I found he was a boxing enthusiast. I found that as an adult he was perennially disorganised and in debt. I found he had a sense of humour and a great kindness where his friends and family were concerned. I found that he was habitually late for appointments, and although deeply religious, usually made the last Mass in Westland Row by the skin of his teeth and the courtesy of the guard at Sandymount Avenue railway station. I came, in short, to feel the contrast between the almost messianic vanity of the man who wrote 'The Singer', and the humanity of the man who was humorous and unpunctual, and who boxed and sang with as much inefficiency as enthusiasm.

[...]

So Pearse died, aged 36, a gentle, humorous man, yet one capable not merely of writing with mystical enthusiasm about bloodbaths, but of actually precipitating one. But if Pearse possessed this split personality, what revolutionary has ever been wholly 'normal'? And if I have suggested that Pearse is overdue for psychological reassessment, I stand on excellent authority in doing so, for he thought so himself. I have quoted his own self-assessment in the Thomas Davis lecture referred to above. I make no apologies for quoting it again: 'I don't know whether I like you or not, Pearse', (he once wrote) 'I think you are too dark in yourself.... Is it your English blood that is the cause of that I wonder.... However, you have the gift of speech. You can make your audience laugh or cry as you please. I suppose there are two Pearses, the sombre and taciturn Pearse and the gay and sunny Pearse.'

(from Patrick Pearse, Le Roux.)

As a self-evaluation, I doubt if that will ever be improved on.

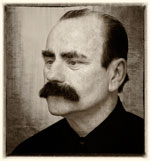

James Connolly (1868-1916)

James Connolly was a self-educated man, who became a revolutionary socialist, a trade union leader and a political theorist. Of the 16 men executed after the Easter Rising in 1916, his death by firing squad, while strapped to an upright stretcher because of his wounds, was perhaps the one that inspired the strongest feelings in Ireland. It contributed to a significant change of public opinion towards the aims and aspirations of the rebels — a change that led ultimately to the establishment of the Irish Republic in the years that followed.

James Connolly

James Connolly 5 June 1868 to 12 May 1916

Connolly's parents were Irish, from Co Monaghan, but he was born in Edinburgh where he lived in poverty. The prospect of a steady wage and his brother's experience in the army led him to join the King's Liverpool Regiment. He was posted to Ireland, from where he deserted, probably because his regiment was due to be sent to India, and he returned to Dundee in Scotland.

He began to read about socialism and the writings of Karl Marx and then joined groups where these matters were discussed. His working life at that time was not as fulfilling or rewarding. Through the efforts of a friend in the socialist movement, he was offered a job in Dublin in 1896 as a paid organiser of the Dublin Socialist Society. Following a speaking tour in America, he emigrated to the US in 1903 where his socialist and nationalist ideas and principles developed further. When he returned to Ireland in 1910 he became involved in the Dublin Lockout in 1913 and in October 1914, after Larkin’s departure for America, he became General Secretary of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) and commander of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA). The headquarters of both organisations were in Liberty Hall, Dublin.

With the outbreak of the First World War, Connolly was one of those who saw that 'England's difficulty is Ireland's opportunity'. Over time he became more of a military strategist and less of a labour organiser. In mid-January 1916, at the meeting which is the subject of the play Pull Down a Horseman, he reached agreement with Patrick Pearse and the Irish Republican Brotherhood Military Council, to co-operate in an insurrection at Easter of that year. He joined the Council, and on the day before the Rising its members appointed him vice-president of the Irish Republic and Commandant-General, Dublin Division, Irish Army.

Connolly was generally regarded as the most effective of the rebel leaders during the Rising. On 24 April 1916 (Easter Monday), he led the Headquarters Battalion from Liberty Hall to the General Post Office and took command of the detailed military operations in the GPO during the week. He was wounded twice, once in the arm and once by a ricocheting bullet in the ankle. That second wound, sustained on 27 April was severe. In spite of this he remained, as Patrick Pearse said, "still the guiding brain of our resistance".

At noon on Saturday 29 April, Connolly was in agreement with most of the leaders of the Rising that they should surrender. He said that he "could not bear to see his brave boys burnt to death".

Connolly was taken on a stretcher to the Red Cross hospital at Dublin Castle. Following the surrender he was court-martialled in his hospital bed on 9 May. At his trial he read a brief hand-written statement in which he said: "The cause of Irish freedom is safe [...] as long as [...] Irishmen are ready to die endeavouring to win [it]". His was the last of the sixteen executions.

Connolly was shot by firing squad at Kilmainham Jail after dawn on 12 May 1916.

Diarmaid Ferriter talking about James Connolly

On 7 March 2016, Diarmaid Ferriter, Professor of Modern Irish History at University College Dublin, was interviewed about James Connolly on the RTÉ Radio 1 programme 'Today with Seán O'Rourke'.

A recording of that interview is in the audio player above.

Research on the meeting between Connolly, Pearse and members of the IRB leadership

In an article published by Century Ireland, Conor O'Malley documented research which he conducted into the circumstances surrounding the secret meeting on which the play Pull Down a Horseman is based.

Author of the research,

Author of the research,Dr Conor O'Malley

The study addresses questions that were first raised within a few years of the Easter 1916 Rising. Principal among those questions was whether Connolly had been 'invited' or 'kidnapped' to attend a meeting with senior leaders of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in January 1916.

The article presents evidence to support the conclusion that Connolly had not been kidnapped. However, the historical records and witness statements cited in the article show that arrangements had been put in place to bring Connolly before the leadership of the IRB by force if necessary, if those sent to 'escort' him to the meeting had found him unwilling to attend.

The research reinforces the validity of the playwright Eugene McCabe’s interpretation and artistic response in Pull Down a Horseman; and it shows how apposite was his comment in the introduction to the script presented as part of the 50th anniversary Easter Rising commemoration programme in 1966: “The three day session, must have been tense, stormy, and mentally exhausting – especially exhausting for Connolly who was one against many”. You can read the article on the Century Ireland website, or download the fully annotated version of the article here.

The 1916 Rising — what it was and what it became

The 1916 Rising was the first major revolt against British rule in Ireland since the United Irishmen Rebellion of 1798. Though some see it as an unmandated, bloody act by unrepresentative secret conspirators, for many it was the founding act of a democratic Irish state. Though the rebels surrendered and 16 of their leaders were executed, the 1916 Rising had a huge effect. It became the first stage in a war of independence that resulted in the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922 and, ultimately, the formal declaration of an Irish Republic in 1949. Diarmaid Ferriter, Professor of Modern Irish History at University College Dublin.

The relevance of Pull Down a Horseman in 2016

At his inauguration as President of Ireland in Dublin Castle on 11 November 2011, President Michael D Higgins noted how James Connolly, 'believed that Ireland was [...] a country still to be fully imagined and invented — and that the future was exhilarating precisely in the sense that it was not fully knowable'. During his address, he underscored the valuable role of creativity in society; and while commenting on Ireland's 'rich heritage' and the importance of 'the ethics and politics of memory', he referred to the challenges and opportunities posed by the forthcoming decade of commemorations for the period from 2012 to 2022 — 'a decade that will require us to honestly explore and reflect on key episodes in our modern history as a nation.'

This new production of Eugene McCabe's play is an entertaining and thought-provoking contribution to such a process.

The above photographs were taken during the recording of the interview with Conor O'Malley on 27 December 2015. The building, which was St Enda's School run by Patrick Pearse, is now home to the Pearse Museum. The room shown is Patrick Pearse's study and the final two images are from the grounds of St Enda's Park in Rathfarnham, Dublin. The videos shown on this page are also available directly at the Dublin Lyric YouTube Channel.

— Declan Brennan

This production of Pull Down a Horseman has been grant assisted by Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council as part of the 1916-2016 Commemoration programme; and the collaboration with Booterstown Community Centre is warmly acknowledged.